By Silas Mwaudasheni Nande

Abstract

Infant malnutrition remains a persistent challenge across many African nations, exacerbated by limited access to safe, affordable infant formula and inconsistent breastfeeding practices. This article evaluates the biochemical suitability of equine milk – specifically mare and donkey milk – as an alternative feeding option for infants unable to access breast milk. It integrates nutritional science, clinical considerations, socio-economic factors, and policy pathways for implementation in African contexts. Comparative profiles with goat and human milk are presented, alongside fortification requirements, safety protocols, and cultural integration strategies. The conclusion argues for a carefully designed research and pilot framework to test fortified equine milk products under African field conditions.

1. Introduction

Across sub-Saharan Africa, the intersection of food insecurity, poverty, and public health constraints has made infant malnutrition a chronic development barrier. In communities where exclusive breastfeeding is not always possible – due to maternal mortality, HIV, displacement, or lactation failure – commercial infant formula is often financially prohibitive and logistically inaccessible. This creates a gap where locally available animal milks enter the conversation as potential substitutes.

Equine milk, derived from mares and donkeys, presents an intriguing candidate due to its biochemical similarity to human milk proteins and its lower allergenic potential compared to ruminant milks such as cow and goat. This article explores the nutritional viability of equine milk, its potential role in African infant feeding strategies, and the critical research and policy steps needed to ensure safety and efficacy.

2. Protein Composition: The Digestive Advantage

2.1 Human Milk Baseline

Human milk proteins are uniquely adapted to the infant gut. The whey-to-casein ratio of approximately 60:40 ensures easy digestion and prevents excessive renal solute load. Whey proteins – such as lactoferrin, lysozyme, and immunoglobulins – play a critical role in immune defense, gut maturation, and nutrient absorption. Casein, while important for calcium transport, forms a tougher curd in the stomach and is harder to digest.

2.2 Equine Milk Protein Structure

Equine milk closely mimics the human whey-to-casein ratio, offering a digestibility advantage. Notably, it lacks beta-lactoglobulin, a major allergen found in cow’s milk. Studies such as Salimei et al. (2004) and Vincenzetti et al. (2011) confirm that donkey milk contains high levels of lysozyme and lactoferrin, contributing to its antimicrobial and immunomodulatory properties. These features make equine milk a promising alternative for infants with cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA), especially in settings where hypoallergenic formulas are unavailable.

2.3 Goat Milk Protein Features

Goat milk, often promoted as easier to digest than cow’s milk, still contains a higher proportion of casein and beta-lactoglobulin. While some infants tolerate it better, its protein structure does not match the immunological benefits of human or equine milk. Research by Park et al. (2007) highlights the limitations of goat milk in replicating the immune-supportive functions of human milk proteins.

3. Fat Content: Neurodevelopment and Energy

3.1 Human Milk Dynamics

Fat is the primary energy source in human milk, averaging 4–5%. It contains essential long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFAs), notably docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and arachidonic acid (ARA), which are critical for brain development, myelination, and visual acuity. The fat content varies within a single feeding, with hindmilk being richer in fat than foremilk.

3.2 Equine Milk

Equine milk has a significantly lower fat content (1–2%), making it less energy-dense. However, its smaller fat globules enhance digestibility. The absence of DHA and ARA is a major drawback, necessitating fortification to meet infant neurodevelopmental needs. Studies by Malacarne et al. (2002) and Martini et al. (2008) emphasize the need for lipid supplementation if equine milk is to be used as a primary infant food source.

3.3 Goat Milk

Goat milk has a higher fat content than equine milk and smaller fat globules than cow’s milk, aiding digestion. However, it lacks the full spectrum of essential fatty acids found in human milk. Fortification remains necessary to support optimal infant development.

4. Carbohydrates and Microbiome Health

4.1 Human Milk Carbohydrates

Human milk is rich in lactose, which fuels brain metabolism. It also contains Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOs), complex carbohydrates that act as prebiotics. HMOs promote the growth of beneficial gut bacteria, inhibit pathogens, and support immune system development. Research by Bode (2012) and Donovan & Comstock (2016) underscores the irreplaceable role of HMOs in infant health.

Human milk is rich in lactose, which fuels brain metabolism. It also contains Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOs), complex carbohydrates that act as prebiotics. HMOs promote the growth of beneficial gut bacteria, inhibit pathogens, and support immune system development. Research by Bode (2012) and Donovan & Comstock (2016) underscores the irreplaceable role of HMOs in infant health.

4.2 Equine Milk

Equine milk has a high lactose content, similar to human milk, but lacks HMOs. This absence limits its ability to support gut microbiota and immune development. Synthetic prebiotics or plant-derived oligosaccharides may partially replicate HMO functions, but cost and efficacy remain concerns.

4.3 Goat Milk

Goat milk contains less lactose than human and equine milk and also lacks HMOs. While lower lactose may benefit infants with rare congenital lactase deficiency, it does not offer the microbiome support provided by human milk.

5. Comparative Nutrient Profiles (per 100ml)

| Nutrient | Human Milk | Equine Milk | Goat Milk |

| Energy (kcal) | 65–70 | 40–50 | 65–70 |

| Protein (g) | 0.9–1.1 | 1.0–1.3 | 3.0 |

| Fat (g) | 4.0–4.5 | 1.0–2.0 | 3.5–4.0 |

| Lactose (g) | 6.5–7.0 | 6.0–7.0 | 4.5–5.0 |

| DHA/ARA | High | Low | Low |

| HMOs | Present | Absent | Absent |

| Beta-lactoglobulin | Absent | Absent | Present |

6. African Public Health Context

6.1 Malnutrition Burden

According to UNICEF and WHO reports, over 45 million children under five suffer from wasting globally, with sub-Saharan Africa accounting for a significant proportion. Exclusive breastfeeding rates vary widely, and formula access is limited by cost, distribution, and water safety concerns.

6.2 Livestock Availability

Donkeys and horses are common in rural African communities, particularly in East Africa (e.g., Kenya, Ethiopia) and Southern Africa (e.g., Namibia, Botswana). Their milk is underutilized despite its nutritional potential. A study by Faye et al. (2018) highlights the feasibility of integrating donkey milk into local food systems.

6.3 Emergency Feeding

In refugee camps, orphanages, and maternal health crises, a safe, locally sourced breast milk substitute could be life-saving. Equine milk’s hypoallergenic profile and digestibility make it a strong candidate, especially where medical infrastructure is limited.

7. Socio-Economic Development Potential

7.1 Rural Equine Dairies

Small-scale equine dairies could provide income for rural households, reduce dependency on imported formula, and improve food sovereignty. Pilot programs in Mongolia and Kazakhstan have demonstrated the viability of mare milk dairies for both nutrition and economic development.

7.2 Gender Implications

Women often manage small livestock and dairy operations. Equine milk production could enhance female economic empowerment, especially if integrated into cooperative models.

7.3 Cultural Acceptability

Cultural perceptions of donkey and horse milk vary. Anthropological studies are needed to assess acceptability and design culturally sensitive education campaigns. In some communities, donkey milk is already used medicinally, which could support its integration into infant nutrition programs.

8. Research and Implementation Roadmap

8.1 Nutrient Fortification Protocols

Equine milk must be fortified with iron, vitamin D, DHA, ARA, and zinc to meet infant nutritional needs. Research should focus on cost-effective, locally sourced fortification methods. Partnerships with universities and agricultural research centers can drive innovation.

8.2 Safety and Processing

Pasteurization is essential to prevent bacterial contamination. Solar-powered pasteurization units and community-based hygiene training can ensure safety. Studies by Griep et al. (2015) show that low-tech pasteurization methods are effective and scalable.

8.3 Clinical Trials

Controlled trials in African contexts are needed to assess growth, neurodevelopment, and morbidity outcomes in infants fed fortified equine milk. Ethical approval, community engagement, and long-term follow-up are critical.

8.4 Policy Integration

If proven safe and effective, equine milk should be included in national complementary feeding guidelines. Ministries of Health and Agriculture must collaborate to develop standards, training programs, and monitoring systems.

9. Case Studies: Lessons from Global and African Contexts

9.1 Mongolia and Kazakhstan: Traditional Mare Milk Use

In Central Asia, mare milk (known as kumis) has been consumed for centuries, both as a nutritional beverage and a medicinal tonic. In Kazakhstan, small-scale mare milk dairies have been formalized into cooperatives, producing pasteurized kumis for local markets. A study by Wanner et al. (2014) found that kumis contains high levels of lysozyme and lactoferrin, contributing to its antimicrobial properties.

Key Takeaways:

- Cultural acceptance is high due to historical use.

- Pasteurization and bottling infrastructure were scaled using local resources.

- Kumis is used therapeutically for gastrointestinal and immune conditions.

Relevance to Africa:

While kumis is fermented and not suitable for infants, the infrastructure and cooperative model offer a blueprint for rural equine dairies in Africa.

9.2 Italy: Donkey Milk for Infants with CMPA

In Italy, donkey milk has been used in pediatric clinics for infants with cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA). A clinical study by Monti et al. (2007) showed that fortified donkey milk supported normal growth and was well tolerated by allergic infants. The milk was pasteurized and supplemented with essential nutrients before use.

Key Takeaways:

- Donkey milk was safe and effective for CMPA-affected infants.

- Fortification with fats and micronutrients was essential.

- Clinical oversight ensured safety and efficacy.

Relevance to Africa:

This model supports the use of fortified equine milk in medical settings, especially where hypoallergenic formulas are unavailable.

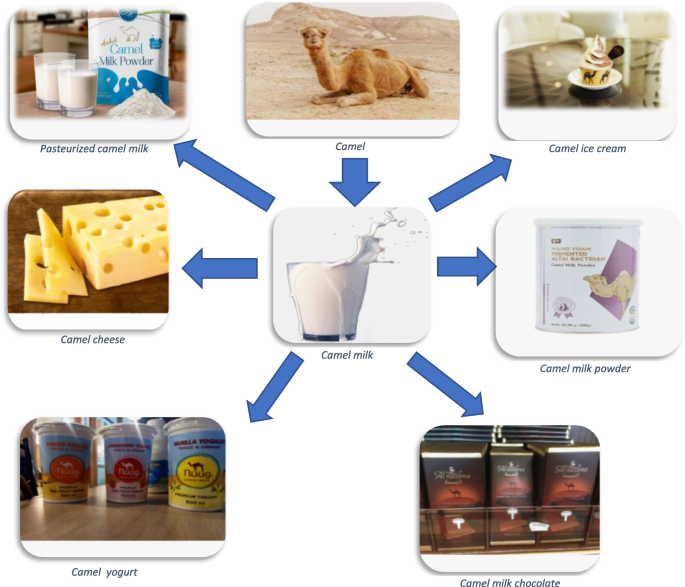

9.3 Kenya: Camel Milk Cooperatives

While not equine, camel milk initiatives in Northern Kenya offer a parallel. Camel milk is collected by pastoralist women’s groups, pasteurized locally, and sold to urban markets. The initiative, supported by NGOs and government agencies, has improved nutrition and livelihoods.

Key Takeaways:

- Livestock-based nutrition can be scaled sustainably.

- Women-led cooperatives enhance community ownership.

- Local processing reduces spoilage and improves safety.

Relevance to Africa:

Donkey and horse milk could follow similar cooperative models, with community-led production and distribution.

9.4 Namibia: Potential for Equine Integration

In Namibia, donkeys are widely used for transport and agriculture, especially in rural regions like Ohangwena, Oshana, Oshikoto and Omusati. While donkey milk is not commonly consumed, its availability and the presence of veterinary infrastructure make it a viable candidate for pilot programs.

Opportunities:

- Existing livestock familiarity could ease adoption.

- School-based nutrition programs could integrate fortified donkey milk.

- Partnerships with agricultural extension services could support training and hygiene protocols.

Challenges:

- Cultural perceptions of donkey milk may require sensitization.

- Initial investment in pasteurization and fortification equipment is needed.

Conclusion

Equine milk – particularly from mares and donkeys – offers a scientifically grounded, culturally adaptable, and potentially life-saving alternative for infant nutrition in regions where breastfeeding is not possible and commercial formula is inaccessible. Its protein composition closely mirrors that of human milk, and its hypoallergenic properties make it especially valuable in vulnerable populations. However, its lower fat content, absence of key fatty acids, and lack of human milk oligosaccharides underscore the need for targeted fortification and rigorous safety protocols.

Africa stands at a unique crossroads: the continent faces high rates of infant malnutrition, yet possesses untapped livestock resources and resilient community structures. By investing in localized equine milk production – paired with ethical research, clinical trials, and community engagement – African nations can pioneer a sustainable model of infant feeding that is both scientifically sound and socially empowering.

This is not merely a nutritional intervention. It is a call to reimagine infant health through indigenous solutions, to elevate rural economies through innovation, and to place the welfare of the youngest citizens at the heart of development. With the right partnerships, policy frameworks, and visionary leadership, equine milk could become more than an alternative – it could become a cornerstone of equitable infant nutrition across the continent.

Silas Mwaudasheni Nande[/caption]

Silas Mwaudasheni Nande is a teacher by profession who has been a teacher in the Ministry of Education since 2001, as a teacher, Head of Department and currently a School Principal in the same Ministry. He holds a Basic Education Teacher Diploma (Ongwediva College of Education), Advanced Diploma in Educational Management and Leadership (University of Namibia), Honors Degree in Educational Management, Leadership and Policy Studies (International University of Management) and Masters Degree in Curriculum Studies (Great Zimbabwe University). He is also a graduate of ACCOSCA Academy, Kenya, and earned the privilege to be called an "Africa Development Educator (ADE)" and join the ranks of ADEs across the globe who dedicate themselves to the promotion and practice of Credit Union Ideals, Social Responsibility, Credit Union, and Community Development Inspired by the Credit Union Philosophy of "People Helping People." Views expressed here are his own but neither for the Ministry, Directorate of Education, Innovation, Youth, Sports, Arts and Culture nor for the school he serves as a principal.

Silas Mwaudasheni Nande[/caption]

Silas Mwaudasheni Nande is a teacher by profession who has been a teacher in the Ministry of Education since 2001, as a teacher, Head of Department and currently a School Principal in the same Ministry. He holds a Basic Education Teacher Diploma (Ongwediva College of Education), Advanced Diploma in Educational Management and Leadership (University of Namibia), Honors Degree in Educational Management, Leadership and Policy Studies (International University of Management) and Masters Degree in Curriculum Studies (Great Zimbabwe University). He is also a graduate of ACCOSCA Academy, Kenya, and earned the privilege to be called an "Africa Development Educator (ADE)" and join the ranks of ADEs across the globe who dedicate themselves to the promotion and practice of Credit Union Ideals, Social Responsibility, Credit Union, and Community Development Inspired by the Credit Union Philosophy of "People Helping People." Views expressed here are his own but neither for the Ministry, Directorate of Education, Innovation, Youth, Sports, Arts and Culture nor for the school he serves as a principal.